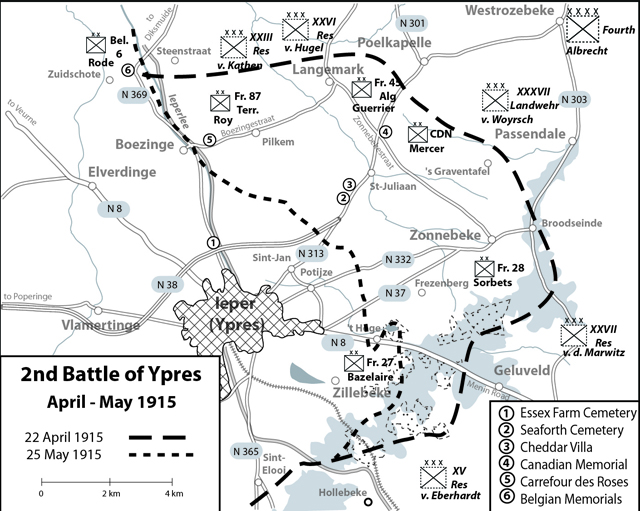

18 Second Battle of Ypres: 22 April to 25 May 1915

Province: West Flanders (West-Vlaanderen)

Country: Belgium

A ‘Virtual Battlefield Tour’ from Fields of War: Fifty Key Battlefields in France and Belgium

Summary: At 17:00 on 22 April 1915, after nervously waiting all day, special German ‘Stinkpionere’ troops observed that the wind had finally turned toward the southwest. A German bombardment struck Ypres and numerous surrounding villages, an event that was unusual but not extraordinary. Six thousand gas cylinders had been secretly collected and placed in the south-facing German trenches from Langemark to Bikschote. A greenish-yellow cloud crept from the German forward trenches to engulf the positions of the French 87th Territorial and 45th Algerian Divisions along the northern shoulder of the Ypres Salient around Langemark. Despite its prohibition by the Hague Convention of 1907, the Western Front witnessed the first military use of poisonous gas.

French troops, gasping and coughing because the chlorine gas tore at their throats and filled their lungs with fluid, immediately began streaming to the rear. The Belgian Grenadiers, who were not as severely affected, held their positions along the canal at the junction with the French and limited the German advance to only a small bridgehead across the canal line. On the French right, the 3rd Canadian Infantry Brigade manned the front lines and held firm.

The panicked withdrawal of French troops left a 6.5 km gap in the front lines. With a single, fearsome action the Germans had opened an unopposed avenue to Ypres. Protected by only a crude respirator that many soldiers did not trust, the German infantry tentatively advanced 3 km and took up defensive positions. General Falkenhayn was so doubtful of the gas’ effectiveness that he allowed for no reserves to carry on the fight. Using the gas late in the day also left little daylight during which to continue the advance. Fate had saved Ypres.

The Germans’ pause gave the Allies time to organize a defense. In their country’s first action on the Western Front, the 10th Battalion Canadian Light Infantry, supported by the 16th Battalion (Canadian Scottish), counterattacked the German 51st Reserve Division’s positions just before midnight in Bois de Cuisiniers (Kitcheners’ Wood), 900 meters west of St-Juliaan. The wood, situated upon the forward slope of the ridge line, was critical territory for controlling the area south of the village. Facing massed machine-gun fire which scythed down the front line, the Canadians pushed on, entering the forest to engage the enemy in hand-to-hand fighting. They cleared the wood at a fearsome cost, losing 613 men out of a complement of 816. Holding the enfiladed position was impossible, however, so they moved back to a trench line on the south edge of the wood.

At 04:00 on 24 April, the Germans released a second cloud against the now Canadian line. Without respirators, the troops desperately wet any available cloth, usually with their own urine, and placed it over their nose and mouth. Despite this crude protection and somewhat effective artillery support, St-Juliaan was overcome by the afternoon.

Counterattacks the next day were met with the usually effective German machine-gun and artillery fire. German batteries took up advanced positions with impunity because their British opponents were chronically short of shells. An assault by the 10th Brigade to retake St-Juliaan led to its almost complete annihilation. In what was to become characteristic of First World War battles, the initially successful advance was followed by both sides throwing more troops into the engagement, resulting in escalating losses for little gain by either side.

The Germans advanced against British positions along the Bellewaerde spur, the last ridgeline before Ypres; from there it was downhill all of the way to the city and beyond. At 06:30 on 8 May, the Suffolk Regiment, manning the forward slope of Frezenberg Ridge, came under heavy bombardment. The firing enveloped the entire salient, while the German assault quickly drove open a 3 km gap in British defenses between Bellewaerde and Mouse Trap Farm. Decimated battalions, random support companies, cooks, and orderlies were ordered into the fight. The line was slowly restored while the attackers settled for establishing their own defenses. By 25 May static positions were once again established. The salient remained, though much reduced in size, and the Germans were only 5 km from Ypres. The British were now compressed into a smaller space that provided German artillery with almost unlimited targets.

The use of poison gas became a fixture on the Western Front. Improved respirators were met with increasingly effective poisons such as phosgene and the notorious mustard gas. Fighting men struggled through engagements encumbered with gas masks that limited visibility and restricted breathing while giving them an extraterrestrial appearance. Could warfare become more horrific?

Battlefield Tour

View 18 Second Battle of Ypres: 22 April to 25 May 1915 '- A Virtual Battlefield Tour by French Battlefields (www.frenchbattlefields.com)' in a larger map

Essex Farm was used as an Advanced Dressing Station from April 1915 to August 1917. Burials were made haphazardly on the ground to the south were the French Army had begun burying its dead during the First Battle of Ypres. The Essex Farm Cemetery was more formally arranged and expanded after the war and now holds 1,204 burials including 5 German nationals. Because most were casualties at the dressing station, only 103 graves are marked as unidentified. (50.871375, 2.872554)

An Albertina Stone in front of the cemetery commemorates Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae, Royal Canadian Medical Corps, who wrote his famous poem ‘In Flanders Fields’ after the death of a close friend during the Second Battle of Ypres. McCrae later contracted pneumonia and died in January 1918, but his poem established the red poppy as a symbol of the sacrifices of the fighting men of the First World War. (50.871284, 2.872559)

The concrete and soil covered dugouts which replaced the timber versions that McCrae would have used as a dressing station are down the lane north of the cemetery and they can be entered. (50.871686, 2.872776)

The British 49th Division Memorial stands upon the elevated canal bank immediately behind the cemetery. The division fought in the area in 1915 and its dead occupy Plot 1 at the northern side of the grounds immediately behind the Cross of Sacrifice marking the entrance. (50.871048, 2.873865)

New Irish Farm Cemetery was used for burials in 1917 and 1918, but by the end of the war contained only 73 graves. After the Armistice, the consolidation of many nearby graveyards, including Irish Farm Cemetery to the immediate south, enlarged New Irish Farm Cemetery to 4,715 burials. Consequently 69 percent of the burials are unidentified. The original graves are formed in irregular rows in Plot 1 about the Stone of Remembrance almost immediately past the entrance. (50.87288, 2.898244)

A true battlefield location, Track X Cemetery, was between the front lines in June 1917 when the British advance toward Passendale started. It’s history accounts for the remote location and irregular shape. The cemetery holds only 149 burials. (50.87811, 2.911184)

British soldiers fighting on the Western Front frequently identified roads and lanes with England language names that they could pronounce more readily that their French or Dutch names. One such small lane was labeled Buffs Road. Buffs Road Cemetery lay along the road and was used by Royal Sussex and Royal Artillery troops between mid 1917 and the German advance of March 1918. Additional graves were added after the Armistice and the cemetery now holds 289 burials. (50.876398, 2.916571)

The farms along the modern highway northeast of Sint-Jan hide the battlefields of 1915. The names given to them by British soldiers — Mouse Trap, Cheddar Villa, Canadian Farm, English Farm, and Irish Farm — resonate through accounts of Ypres battles.

Approximately 1 km before entering St-Juliaan is Cheddar Villa Cemetery, now known as Seaforth Cemetery. The Canadian 10th Battalion formed-up here before their assault upon Kitchener’s Wood. The location also experienced heavy fighting on 25 and 26 April 1915 when 2nd Battalion Seaforth Highlanders attempted to recapture St-Juliaan; their dead were buried here. As the site of later fighting, many of the original graves were obliterated. The stones in the open central area mark what are essentially mass graves. The surrounding flat and open terrain demonstrates the difficulty in advancing against an entrenched enemy, especially one who possesses artillery superiority as the Germans did in 1915. (50.879978, 2.926802)

Immediately adjacent to the cemetery is a farm known as ‘Cheddar Villa’ to the British. On the far (northern) side of the farm is a large German blockhouse which was part of a string of pillboxes stretching across the field to the north. Captured at the opening of the Third Battle of Ypres, it became a British Advanced Dressing Station and suffered a terrible fate when a German shell entered the open doorway — since it was constructed by the Germans, the opening faced toward their lines — and exploded among sheltering soldiers, the wounded, and the medical staff. (50.88097, 2.92673)

Kitcheners’ Wood is marked only by a white stone memorial plaque along a rural road that proceeds north from the vicinity of Seaforth Cemetery. The memorial stone, in the shape of an oak leave, stands at the corner of a farm complex. (50.8876, 2.918887)

St-Julien Dressing Station Cemetery was in used as medical facility when the German gas attack occurred. The position was lost the German advance of 24 April 1915 to be recaptured later that year. The cemetery was started in September 1917, but the German advance of 1918 overtook the area once again. The graves were damaged by shellfire in the engagement. The grounds now hold 420 burials of which 180 are unidentified. The irregular plots and special memorials attest to the battlefield nature of the grounds. (50.887625, 2.935388)

On one corner of Vancouver Corner, which was also the site of the Triangle defensive works, stands the famous Canadian Memorial at St-Juliaan, popularly known as ‘The Brooding Soldier.’ The 11-meter granite pillar is surmounted by the head and shoulders of a soldier with head bowed and hands resting upon arms reversed — the traditional funeral stance. The top is illuminated at night, adding to the already sorrowful yet determined mien of the battlefield’s guardian. The attached plaque states: ‘This column marks the battlefield where 18,000 Canadians on the British left withstood the first German gas attacks the 22nd – 24th April 1915. 2,000 fell and lie buried nearby.’ The stone, marked with directions to sites on the battlefield, sits upon a stone court, which in turn is surrounded by a grass lawn and clipped hedges. In the two days that the Canadians defended the line against German artillery and gas, they suffered a total of 6,037 casualties but proved themselves as a formidable fighting force. (50.899587, 2.940207)

The Le Carrefour des Roses contains the Breton Memorial, a commemoration of the two French divisions which experienced the initial gas attack of 22 April. The site also has a prehistoric dolmen and 16th century calvary, both relocated from Brittany, the home of the 87th Territorial troops. (50.897297, 2.874176)

Artillery Wood Cemetery was begun by the British Guards Division after the Battle of Pilckem Ridge in July 1917. The ground to the north of the wood was a front line cemetery until the German advance of March 1918. By war’s end, it held only 141 graves, but it was enlarged after the Armistice such that it know contains 1,307 burials with 506 of those unidentified. The cemetery is known for the graves of two wartime poets, Francis Ledwidge and Hedd Wyn. (50.899639, 2.872474)

A memorial to Irish poet Francis Ledwidge stands along a bicycle path. Ledwidge was killed by a shell explosion while working near Le Carrefour des Roses. He is buried in the nearby Artillery Wood Cemetery. (50.897909, 2.873734)

Boezinge was on the front line from the Battle of Yser to the British Offensive of 1917. At the intersection a Demarcation Stone (50.893712, 2.8593) identifies the farthest German advance. An ivy-covered blockhouse is behind the stone with a German mortar mounted upon its roof as a post war souvenir. (50.893655, 2.859216)

A memorial stone commemorating the French 418th Regiment was erected after the war. The stone’s graphic depiction of gas victims holding their eyes in agony offended the Nazis, so German soldiers blew up the stone during their occupation in 1941. It has been replaced by a simpler, 15-meter aluminum cross erected upon a stone-banked earthen mound. The Franco-Belgian Memorial is inscribed with French and Belgian units which were subjected to the gas attacks. (50.918285, 2.840997)

A granite obelisk commemorates the Belgian 2nd Grenadier Regiment who manned the extreme right of the Belgian line on 22 April and whose men fought off the effects of the gas to repel the German attempt to cross the canal. (50.921414, 2.835206)

A black sword mounted upon a white stone cross is dedicated to the men of the Belgian 3rd Regiment who fell defending the canal line. (50.919556, 2.843659)

The Belgian 3rd Division Monument commemorates that unit’s participation in the Battle of the Yser. (See Virtual Tour #15) The division spent much of the war defending the canal line from German advance. The metal panel affixed to the stone carries the names of divisional units. (50.945492, 2.861666)

Copyright 2014

Presented by

French Battlefields

Publishers of

Fields of War: Fifty Key Battlefields in France and Belgium

Web: www.frenchbattlefields.com

Blog: www.frenchbattlefields.com/blog